|

Below

are highlights of three dramatic

nationally-publicized criminal cases I tried

and have written of in my memoir as a defense

attorney.

_______________________________________________________________________________

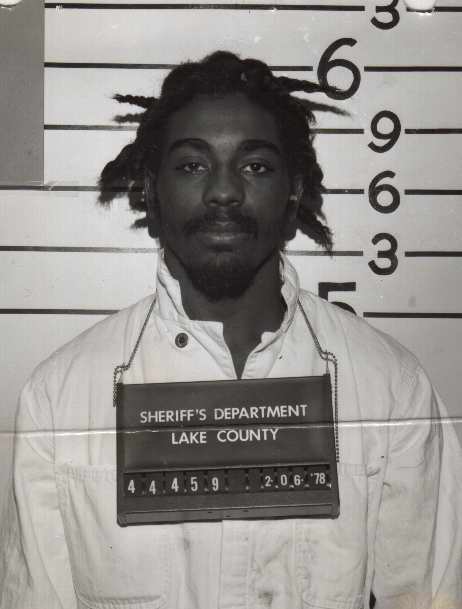

Look into the eyes of this

good young man, then clearly understand this:

Although absolutely innocent, Larry Hicks came

within four days of being executed in

Indiana's electric chair for supposedly

stabbing two men to death in a fight inside a

Gary home. At trial, he was represented by a

public defender who wholly failed to

investigate the case, did not know Larry faced

the death penalty until a week before trial,

and then presented little to no defense. This,

though one was available.

After Larry was convicted

in a day-and-a-half trial and sentenced to

death by the judge when the jury could not

decide on a penalty, the PD failed to

initiate any appeal and had

not applied for a stay of execution by the

time I met Larry at precisely* the

essential moment and immediately got involved.

A stay of execution was granted; and, after I hired the recently retired polygraph expert from the Indiana State Police Department and later the nation's top polygraphist at the Keeler Institute in Chicago to run tests on Larry, both concluded that Larry was telling the truth when he claimed he was not involved in the double homicide. With that information in hand, I was awarded a grant from the Playboy Foundation to help defray expenses after Playboy magazine's senior editor, Bill Helmer, had a private detective conduct a preliminary investigation into the case as well as Larry himself. Then, a few months after the trial judge was persuaded at a hearing to grant a new trial, Helmer published an article about the matter titled “The Man Who 'Didn't Do It'” in the August 1980, issue of Playboy. At Larry Hicks' new trial, in my opening statement I reminded jurors of the judge's earlier instructions that the burden of proof was on the state to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt and that the defendant had no burden to prove anything at all and then told them that, in this case, the defense would accept the burden of proof and affirmatively prove that Larry was innocent – which we did, in spades. Then, after Larry was found not guilty and the jurors were still in the courtroom about to leave that night, I invited them and the judge to celebrate the acquittal at the Holiday Inn, and 11 of the 12 jurors and the judge (the same one who had once sentenced Hicks to death) celebrated with Larry and the defense team, with the last people leaving after the sun came up the next day. A Chicago newspaper promptly blared the front-page headline "A lawyer snatches man from Death Row" and an Indianapolis newspaper wrote, "Forgotten man is rescued from death row." Bill Helmer's second article, published in the May 1981, issue of Playboy was “The Ordeal of Larry Hicks.” ~~~~~

Special

note: Larry Hicks was a deeply

religious man who prayed for God to

help him and got others to pray for

him as well. We met* by mere coincidence (some

people will think, but consider the

previous sentence and below) a mere

eight days before he was set to be

executed. He was sure that God sent me

to save his life and told this to a

psychiatrist, who told Larry that he

probably should not mention it to the

judge at an upcoming pretrial

competency hearing or the judge might

think he was crazy. _______________________________________________________________________________ The Shocking Insanity

Defense This was one of the more highly publicized cases of the 20th century.

Interest in the Tony

Kiritsis case of 1977 persists to this day

due to the spectacular nature of what he

did (kidnapped a mortgage company

executive in his downtown office, wired a

sawed-off shotgun to his neck, marched him

around the icy streets of Indianapolis,

then held him hostage for 63 hours),

several terrifying lengthy portions of

which were broadcast live on radio and

television. In 2017, Alan Berry and Mark Enoch co-produced the award-winning documentary titled “Dead Man's Line: The True Story of Tony Kiritsis.” That same year, Richard Hall (Tony's kidnapped hostage) published Kiritsis and Me: Enduring 63 Hours at Gunpoint, with Lisa Hendrickson. In early 2022, actor Jon Hamm co-produced and voiced the role of radio talk show host Fred Heckman (who aired Tony's obscenity-laden rants), in a podcast of eight episodes titled “American Hostage” written up favorably in Variety, GQ, and elsewhere. I blasted Hamm's podcast in an op-ed piece for the Indianapolis Star.

The “not guilty by reason of insanity” verdict stunned almost everyone, especially because Kiritsis had repeatedly shouted over the airwaves that he was not crazy, knew perfectly well what he was doing, was getting revenge for having been cheated – and had made detailed written plans to do exactly what he did.

When the verdict was

returned on October 21, 1977, it was promptly

announced during a break in an NBA basketball

game going on in Indianapolis between the

Indiana Pacers and Chicago Bulls,

and the stadium erupted in a standing ovation

of loud clapping and cheers. The outcome was

hugely popular both locally and nationally,

but many politicians, business people, and

others thought the verdict was outrageous. The Case of the

Highly Talented Rick

Curry of Venice, Florida, was the “Ace,”

allegedly the main pilot and trainer of other

pilots for the international drug smuggling

organization known as The Company. The federal

government claimed that he had flown multiple

tons of drugs, primarily marijuana, from

Colombia and Mexico into Florida, Texas, and

elsewhere on several occasions over a period

of years. He was charged in federal court with

conspiracy to smuggle narcotics, smuggling

narcotics, and possession of narcotics. In an effort to pressure Curry into pleading guilty, the government also charged him as a “dangerous special offender” claiming his piloting skills were “critical to international narcotics smuggling,” a charge that mandated an enhanced sentence of 25 years to life imprisonment and could be read to the jury only in the event of convictions on the underlying charges. Of

Curry's 16 co-defendants, only one other pleaded

not guilty. All others entered guilty pleas

and went to prison, several of whom agreed to

testify against him yet still went to federal

prison for at least two years, some for five,

one for ten. But

Rick pleaded not guilty. I interposed a

coercion defense for him, and he testified on

his own behalf and admitted to making the

smuggling trips the government's witnesses

claimed and, further, to getting paid a great

deal of money for those trips. Curry

testified that he had no alternative but to

make the trips else he, and likely his wife,

would have wound up as alligator bait in the

swamps of south Florida or in Biscayne Bay

wearing concrete shoes. The evidence regarding

Curry's flights was dramatic: E.g.,

getting forced down over Colombia by its Air

Force, captured by Air Force ground security

then stolen from them by threat of superior

force by the Army, then freed when a smuggling

organization paid a large bribe for Curry's

release. Curry's not guilty verdicts outraged the district court judge (who had generally acted as co-prosecutor) so much that he told the jurors to join him in chambers after they were excused and then excoriated them for the verdicts, causing one juror to cry and try to change her vote. Which conduct was reported to the chief judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Chicago, who gave the district court judge a written reprimand, with a cc: to defense counsel.

These verdicts of acquittal for a smuggling pilot based

on a coercion defense are, to the best of my

knowledge, the only such acquittals in United

States history. I served as counsel for Rick

Curry in four states.

_______________________________________________________________________________

~Nile Stanton A succinct

biography is available here:

|