|

~~~

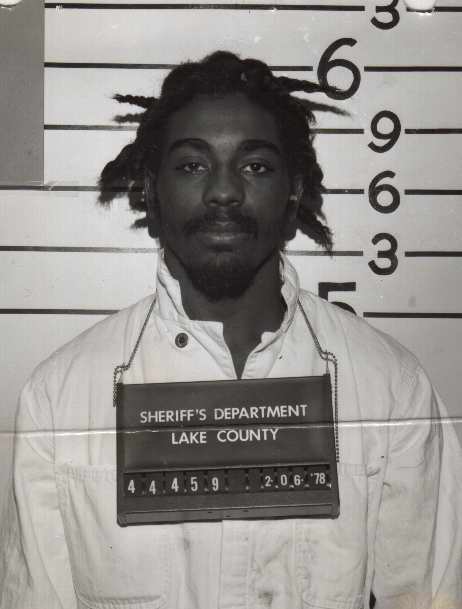

The Death Penalty Case of Larry Hicks

Look into the eyes of this good young man, then

clearly understand this: Although

absolutely innocent, Larry Hicks came

within four days of being executed in

Indiana's electric chair for supposedly

stabbing two men to death in a fight

inside a Gary home.

At trial, he

was represented by a public defender who

wholly failed to investigate the case, did

not know Larry faced the death penalty until

a week before trial, and then presented no

defense. This, although a solid one was

available.

After

Larry was convicted in a day-and-a-half trial and

sentenced to death by the judge when the jury

could not decide on a penalty, the PD failed to

initiate any appeal and had

not applied for a stay of execution by the

time I met Larry at precisely the essential moment and

immediately got involved. A stay of execution was granted; and, after I hired the recently retired polygraph expert from the Indiana State Police Department and then the nation's top polygraphist at the Keeler Institute in Chicago to run tests on Larry, both concluded that Larry was telling the truth when he claimed he was not involved in the double homicide. With that information in hand, I was awarded a grant from the Playboy Foundation to help defray expenses after Playboy magazine's senior editor, Bill Helmer, had a private detective conduct a cursory investigation into the case as well as Larry himself. Then, a few months after the trial judge was persuaded at a hearing to grant a new trial, Helmer published an article about the matter titled “The Man Who 'Didn't Do It'” in the August 1980, issue of Playboy. At Larry Hicks' new trial, in my opening statement I reminded jurors of the judge's preliminary instructions stating that the burden of proof was on the state to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt and that the defendant had no burden to prove anything at all and then told them that, in this case, the defense would accept the burden of proof and affirmatively prove that Larry was innocent – which we did, in spades. Then, after Larry was found not guilty and the jurors had been excused but were still in the courtroom about to leave that night, I invited them and the judge to celebrate the acquittal at the Holiday Inn, and 11 of the 12 jurors and the judge (the same one who had once sentenced Hicks to death) celebrated with Larry and the defense team, with the last people leaving after the sun came up the next day. A Chicago newspaper promptly blared the front-page headline "A lawyer snatches man from Death Row" and an Indianapolis newspaper wrote, "Forgotten man is rescued from death row." Bill Helmer's second article, published in the May 1981, issue of Playboy was “The Ordeal of Larry Hicks.” ~~~~~

Special note: Larry

Hicks was a deeply religious man who

prayed and prayed for God to help him and

got others to pray for him as well. We met by mere

coincidence (supposedly, but consider the

previous sentence and below) a mere eight

days before he was set to be executed. He

was sure that God sent me to save his life

so had no worries about the outcome of the

upcoming new trial and told this to a

psychiatrist, who told Larry that he

probably should not mention it to the

judge at an upcoming pretrial competency

hearing or the judge might think he was

crazy. ~Nile Stanton For highlights of two more of the six nationally-publicized trials I had, click here.

|